On the Problem of Growing True

Hildegard Wildebeast on Tanya Rotherfield’s F1 Series

One approaches Tanya Rotherfield’s F1 Series with the mild expectation of resemblance — after all, we are told that these works share a common parentage, that they originate in the observation of the same organic subject. And yet, standing before their upright congregations, arranged in slender familial columns, one quickly abandons the hope that likeness might prevail.

The F1 hybrid, as any gardener will tell you (and I have been told this, repeatedly, by a man in Braga with a tragic relationship to courgettes), is a child that will not grow true. It bears within it the genetic promise of divergence — a polite refusal to return to type. Rotherfield’s drawings enact precisely this condition. Each small square proposes itself as kin to the next, but only in the loosest hereditary sense: a shared inclination toward coagulation here, a tendency to filamentary outgrowth there. No form is repeated so much as misremembered.

There is, in many of these works, the sensation of something attempting to come into being and encountering difficulty in the attempt.

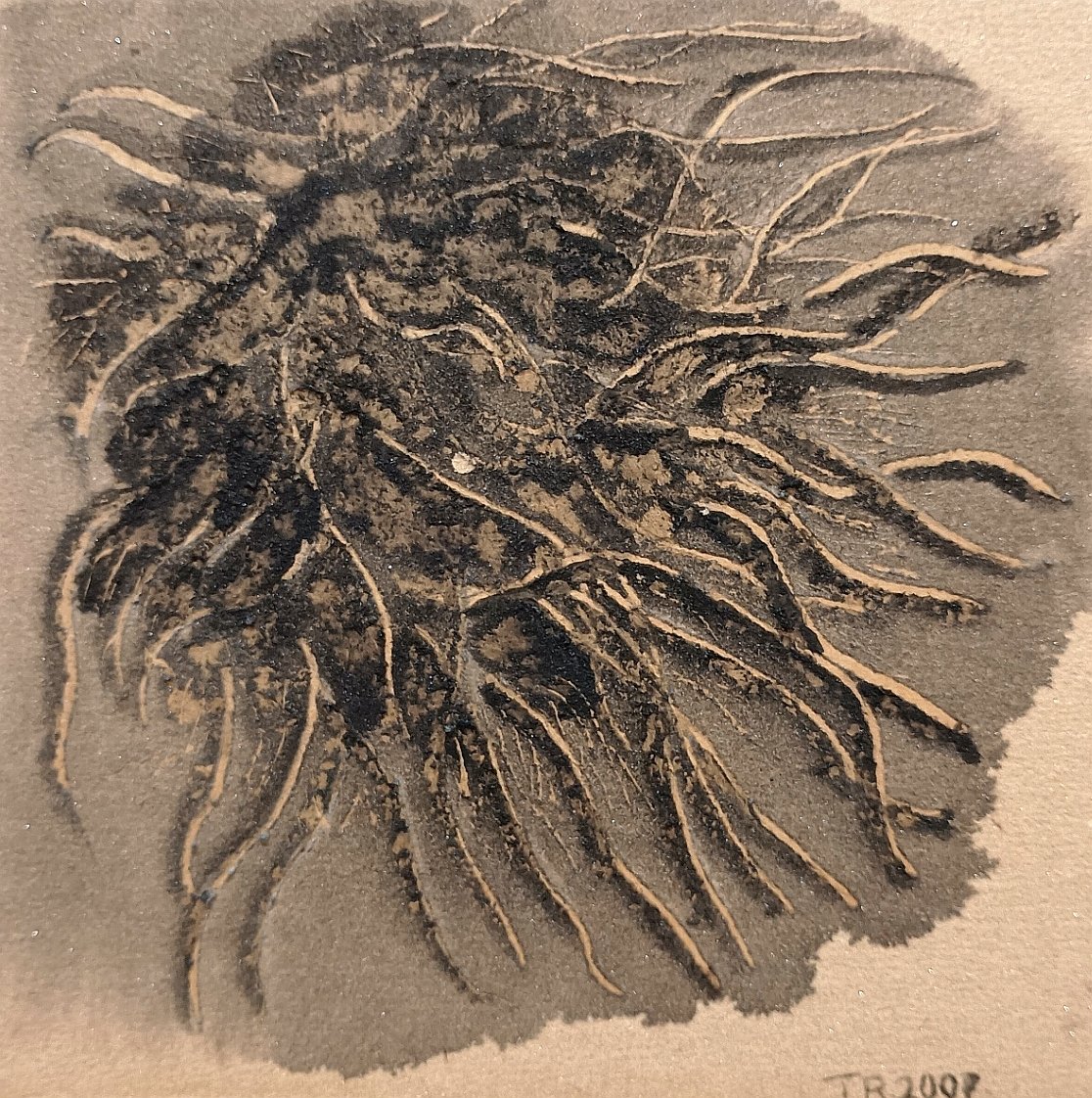

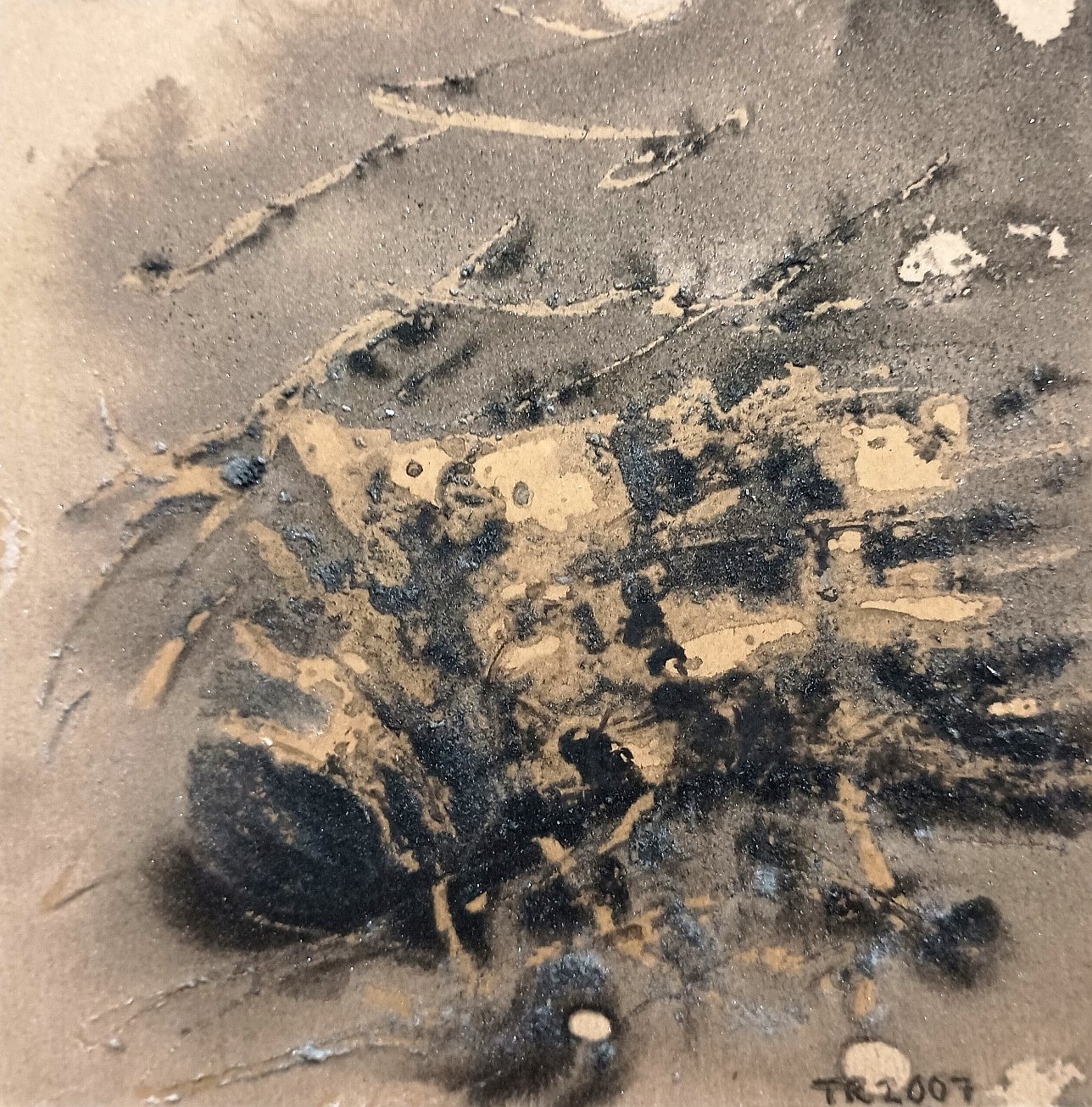

Pigment pools, then stalls. Graphite gathers itself into particulate murmurs that hover uncertainly between atmosphere and terrain. Pencil lines venture outward from darker centres in pale, root-like excursions, only to snag or dissipate along the abrasive topography of the sandpaper ground. One becomes acutely aware that this is a surface which does not welcome the image so much as negotiate its arrival. The mark must persuade its way into existence, contending with the minute resistances of grit and tooth.

Some forms appear almost geological — dense, circular accretions embedded as though under pressure — while others remain diffuse, hovering at the threshold of visibility like a spore cloud caught mid-drift. Across the series, behaviours recur without stabilising into identity: branching, blooming, sedimenting. Each drawing seems to test the same proposition under slightly altered material conditions, producing outcomes that are related but never resolved.

Seriality, here, does not operate as system but as propagation.

That each of these “first children” may be individually acquired introduces an afterlife of dispersal. Removed from their wall-bound colony, they will take root in new domestic ecologies, continuing their quiet divergence elsewhere. One suspects they will remain stubbornly themselves — or rather, stubbornly untrue.

Rotherfield’s drawings do not describe organic life so much as inherit its habits: variation, contingency, and the persistent failure of resemblance to guarantee return.