SYNAESTHESIA

Elizabeth Haines

Oct 18th - Nov 22nd

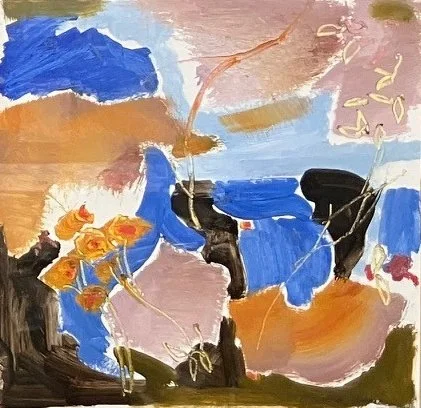

Elizabeth Haines has developed a distinctive voice that balances observation, poetry, and imagination. Her work straddles the boundary between representation and abstraction: drawing from the landscapes of Wales, informed by years sketching from nature, yet transformed through memory and dreams.

Elizabeth's art is rich in texture, colour, and inner space. Her studio practice is deeply connected to her surroundings: the rugged terrain, changing light of Pembrokeshire feed her work, but so too do poetry and music

Her paintings invite the viewer in: at first through colour, surface, and form; then deeper, toward architecture, trees, or horizons suggested rather than stated.

SYNAESTHESIA

Synaesthesia: someone asked me, is it a gift or an affliction? I think it’s both, but it’s certainly a gift for an artist. This ‘meeting of the senses’ takes a unique form with everyone who suffers from it. Some people have an irrevocable association between colours and numbers, or colours and days of the week; some can ‘taste’ sounds, and others hear certain notes when seeing a particular colour, or ‘see’ a scent. It means that the sense modalities, usually located in different areas of the brain, somehow leach into each other.

For me it is seeing the shapes of music, the infinitesimal spaces between phrases or single notes, or the changes in speed and dynamics which can so affect an interpretation. If a colour in my picture is just wrong, then I can see the violinist finely tuning their instrument till it chimes perfectly, and use that image as I work.

Of course in painting or any visual art there is no such thing as the note ‘A’ vibrating at 440 Hertz, today’s ‘concert pitch’, required by musicians to tune in harmony. Painters have no such exactitude to fall back on, but nevertheless there is so much which we can learn from the sister arts of music and poetry. We might ‘see’ the crucial space between the musical lines, or appropriate the notion of rhyme and alliteration and turn it towards visual repetition, as I did when making ‘A piece of work which conveys the nature and genius of Cerdd Dafod’ (Welsh Prosody) for the 1986 National Eisteddfod. In that case, it was very useful to be a Welsh language learner, as I could hear the music of the poetry before understanding the content. That came later, together with an understanding of how in Welsh poetry there is an extraordinary and unique parity between sound and sense.

Years of drawing at music rehearsals, and talking to composers and performers, gave me so many more insights: remarks such ‘It’s the spaces between the beats which are important’ and ‘If you blow hard you will make the note go out of focus.’ ‘Which ending shall we do today? Let’s have the one where the themes come together in a different key...’ and ‘Are you really going to finish on an unresolved dominant 7th?’ and so on. I was also fascinated by the possible analogies between tonality and perspective, where, in both cases you start from a ‘home’: and may or may not return to it.

In the arts synaesthesia can be closely associated with metaphor, the perceiving of one thing in terms of another, perhaps more familiar, in order to illuminate meaning. Cross-modal analogies are widely used to illuminate our speech: ‘I’ve got the blues’; ‘I smelt a rat in that equation’ (said to me by a physicist), or ‘He was completely tone deaf to the situation.’

Many wonderful art works contain a wealth of allusions to other sense experiences, and practitioners such as Baudelaire, Kandinsky and Schoenberg were particularly excited by them – far too many to mention here. Anybody who would like more detail is welcome to read my PhD thesis ‘The Web of Exchange’, University of Wales 2001.

I really hope you enjoy this exhibition, and find some new ideas to take home, whether or not you are afflicted by synaesthesia.

Elizabeth Haines October 2025